Art History for Chapter 11:

Mastery of the Machine: The Industrial Revolution, 1764 to 1914

The rise of industrialization provoked several reactions in art. Indeed, this period experienced the most diverse explosion of diverse creativity in the visual arts ever. Numerous movements of artists permanently fractured High Art, allowing diverse approaches of painting and sculpture which are enshrined in museums of contemporary art today. The increasing production of wealth also allowed “low” art to proliferate and survive among the growing middle and working classes. As the century progressed, art moved in completely new directions.

Contrasted to the poised calm of Neo-classicism, Romantic art, became charged with emotion, violence, passion, except where it turned to mystic contemplation. The Romantic Movement also revived interest in the Middle Ages, which the Renaissance had attacked with its revival of classical antiquity. Romantics found much to admire in medieval times, especially their conception of deep Christian faith, now shown as meditations on the ruins of medieval abbeys in wilderness and heath. The ideal artist was characterized as the genius, expressing the true meaning of things, pursuing art for art’s sake.

The Pre-Raphaelites (1848-1900) represented the highpoint of this movement in England.

Painting/Graphic Arts

Romantic painting largely used naturalism, yet foreign or fantastic subjects often expressed more emotional passion. The art often acknowledged its artificial nature, as brushstrokes might be obvious, or colors more bright and rich than in reality. Watercolor works also began to become popular, helped by high quality rag paper and the ease of carrying the pigments.

Machine manufactured paints in tubes also allowed artists to leave the studio and paint directly from nature.

The landscapes of John Constable (b.1776-d.1837) capture rural English life at its most idealized.

The paintings of Caspar David Friedrich (b.1774-d.1840) capture longing for the quiet of nature.

The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault (b.1791-d.1824) illustrates the drama of a contemporary shipwreck. Both the survivors and the dead crowd a sea-tossed raft as possible rescue appears.

The unique artist J. M. W. Turner (b.1775-d.1851) moved beyond Romanticism to pave the way for a more interesting artistic future using light and color. See “Rain, Steam, and Speed – The Great Western Railway” shows the modern world racing out of the mist. Or “The Fighting Temeraire” mourns for the last remnant of a golden past.

Architecture

The Romantic movement encouraged a great deal of building in a style called Neo-Gothic, since it imitated that form of late medieval architecture. Many unfinished cathedrals were finally completed in the Nineteenth Century and many new ones, especially in America, imitated the medieval style.

The Houses of Parliament in London are perhaps the most famous example of the Neo-Gothic style.

B. ART NOUVEAU and SYMBOLISIM (1890-1914)

The Art Nouveau movement (in Germany Jugendstil in Austria Seccession) at the end of the century (1890-1914), continued the trend, especially in emphasizing handcrafts and natural forms: insects, flowers, and other plants.

Art Nouveau style elements decorated many late -Nineteenth and early-Twentieth Century buildings and even subway entrances.

Connecting Art Nouveau, expanding on Romanticism, reacting against Realism, and anticipating impressionism and expressionism was the movement of Symbolism. These artists painted recognizeable figures and themes, often drawing on mythology and spiritualism, yet embued them with sensuality, mystery, melancholy, and even morbidity. The symbolic meaning is not based on commonly accepted tropes, but may depend on the obscure or unknowable intention of the artist. Franz von Stuck's "Sin" has a snake-draped woman embody the feeling.

C. REALISM (1850-1900)

The movement of Realism reacted against Romanticism. Realist artists, of course, used naturalism, but also tried to portray the world as they thought it really was, often focusing on contemporary social problems. They turned away from fantasy and mythology, using the peasant and working class for subjects. Many of them also battled with the established art critics who dominated through the media and the academies of art and preferred Neo-classicism and tame or nationalized Romanticism. The official critics considered the art of realists as too lowbrow and lower class rather than ennobling and inspiring.

Painting/Graphic Arts

Gustave Courbet (b.1819-d.1877) shocked accepted ideas, painted what he could see, not angels or ancient Romans. Focus on common, even vulgar people. When the exhibit at the World Fair of 1855 rejected his he opened his own “Pavillon du Realism”--first time an exhibit was dedicated to one artist.

The American James Abbot McNeill Whistler (b.1834-d.1903) promoted the art for art’s sake idea. He lived an archetypical bohemian lifestyle. His “Arrangement in Gray and Black No. 1 or Whistler’s Mother” consciously moved toward the abstract, away from the individual and narrative (although it remains popular today probably because of our attachment to the person still there, not the style).

The most revolutionary development in this period was the invention of the photographic camera in the 1830s in France by Niépce and Daguerre. The ability to simply capture a close approximation of how nature actually appeared to the human eye, soon forced artists to reinterpret art as a personal expression of the essence their work (see the Impressionists).

Photography also became an art, especially since the constraints of cameras and film (originally using shades of gray and a limited frame of view) also required interpretive interaction between artist and subject.

The beginning of contemporary art comes with Impressionism, popular more than a hundred years later. At first, critics and public despised the new style. A group of artists experimenting with visual techniques exhibited at the 1874 Exposition in Paris. Critics insulted their offerings as “L'exposition des Impressionnistes.” The new artists, and later historians, adopted the term as a name for their breaking away from traditional forms of visual arts.

Painting/Graphic Arts

Impressionism made its biggest impact in painting. They reacted against the strict naturalism of most art since the Renaissance, as well as the new objectivity of the camera. Viewing through the artist’s eye, they tried to reinterpret the underlying reality of nature through color and light, often with large and obvious brushstrokes. Their art rarely illustrated a story. Instead they tried to capture the feeling or essence of a field, a church, or a street scene. They took their easels out into the real world to capture the play of light and air at different times of the day or weather.

The foremost impressionist was Claude Monet (b.1840-d.1926) whose painting “Impression: Sunrise” led to the name of the movement.

Sculpture

The human figures done by Auguste Rodin (b.1840-d.1917) may appear at first glance naturalistic, but they contain unnatural angles and disproportions as he tried hoped the way light hit or the eye read his sculptures would make them appear realistic. His most famous sculpture is The Thinker, here in a version damagedby a bomb.

Also, Degas achieved some success turning his drawings of ballerinas into bronze sculptures.

The Impressionists were followed by three great artists who are so unique they stand on their own, but are often grouped together under the term POST-IMPRESSIONISM.

Paul Cézanne (b.1839-d.1906) portrays nature as formed of geometric shapes (cylinders, cones, spheres, planes).

Paul Gauguin (b.1848-d.1903) used his trips to French colonies in the south Pacific to inspire exotic visions of dreams and emotion. One famous painting asks the meaning of life: “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?”

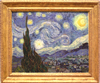

The art of the Dutch Vincent Van Gogh (b.1853-d.1890) remained unappreciated in own lifetime. Recently, his paintings are among the most expensive ever sold. Perhaps connected to migraines and mental illness, He paints with swirls, thick blobs, and brilliant color, slightly off from normal perception. As he wrote to his brother he purposefully intended to “exaggerate the essential, and to leave the obvious unclear.” His probably most famous work “Starry Night” (which also inspired a pop song in the 1970s).

The art of the Dutch Vincent Van Gogh (b.1853-d.1890) remained unappreciated in own lifetime. Recently, his paintings are among the most expensive ever sold. Perhaps connected to migraines and mental illness, He paints with swirls, thick blobs, and brilliant color, slightly off from normal perception. As he wrote to his brother he purposefully intended to “exaggerate the essential, and to leave the obvious unclear.” His probably most famous work “Starry Night” (which also inspired a pop song in the 1970s).